In order to understand Pelé’s position on field, it is necessary to explain the tactical formation of Brazilian football during his reign. Almost every Brazilian team played in a 4-2-4, organized like this (adapted, not literal translation): goleiro (goalkeeper); lateral direito (right-back), quarto-zagueiro (centre-back on the left), zagueiro central (centre-back on the right) and lateral esquerdo (left-back); médio-volante (defensive midfielder) and meia-armador (midfield playmaker; also called meia-direita); ponta-direita (right winger), centroavante (centre forward), ponta de lança (literally “spearhead”, to be explained later) and ponta-esquerda (left winger) — about the origin of such terms, I recommend reading an article in Portuguese written by experienced Brazilian journalist Alberto Helena Júnior).

The most traditional number assignment from midfield to attack was this: 5, volante; 8, meia-armador; 7, ponta-direita; 9, centroavante; 10, ponta de lança; and 11, ponta-esquerda. About the number 10, it is important to inform that it only became a synonym of the ponta de lança after Pelé wore it in 1958 (Brazil’s numbers were determined randomly).

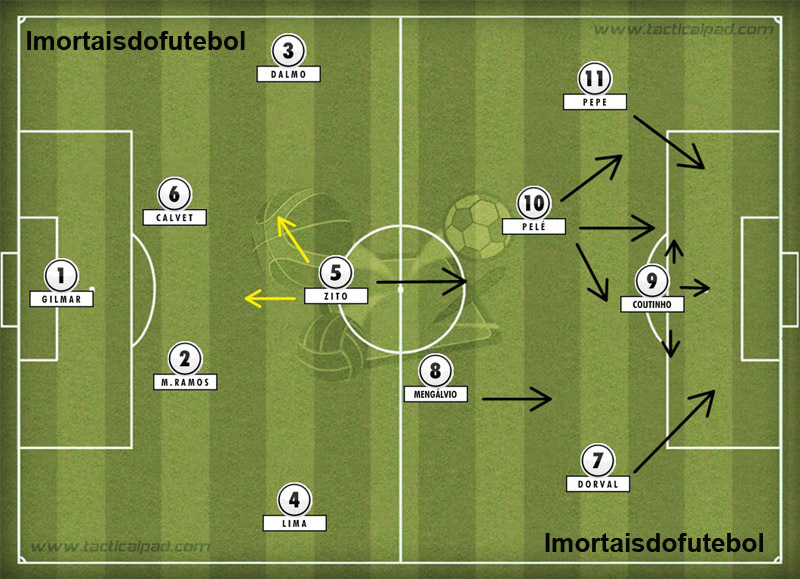

Botafogo, Brazilian Champions in 1968, and the Santos, that won basically everything in 1962, strictly followed that criteria (none the less, some teams, like Cruzeiro, used to invert numbers 8 and 10: Tostão, ponta de lança, played with the 8, Dirceu Lopes, meia-armador, wore the 10):

In this classical formation, the team’s main organizer was the meia-armador (responsible mainly for playmaking; usually did not score much). However, the ponta de lança (regularly the team’s leading scorer), besides going forward to make plays with the centroavante, had a double job, because he also went back to help the meia-armador in making plays; that was the famous “8 and 10” duo in the midfield.

To illustrate what was explained above, Santos formation in 1962 (very nice work done by the excellent webpage “Imortais do futebol“; personally, I would add an yellow arrow going back for Pelé, showing his retreating to midfield during parts of the game):

One can notice that, during a significant part of the game, the ponta de lança played behind three other forwards (pontas and centroavante), specially when coming back to make plays. When he went on to the attack, he would make a duo with the most advanced player, the centroavante.

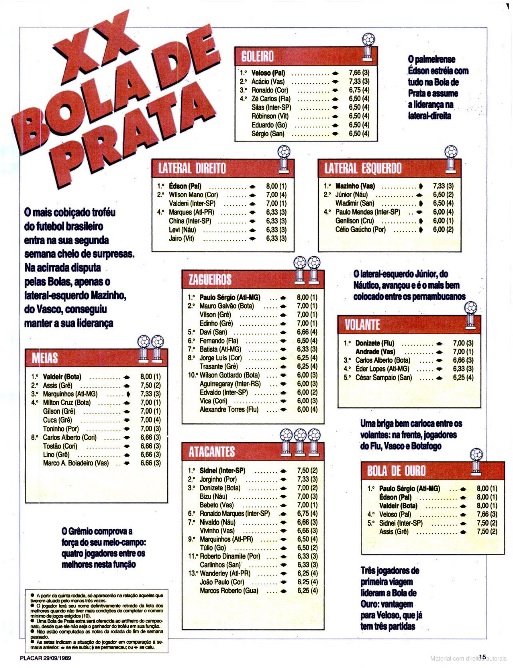

Few Brazilians know that this division of roles remained predominantly in Brazilian football until the end of the 80’s. In 1988 it was still used for the “Bola de Prata”, awarded by “Revista Placar” (the most famous football magazine in the country) to best players (by position) of the national league (notice that the great Zico is in the list as a ponta de lança; pay attention, those are only the preliminary results from that year):

Only in 1989, (picture below), the magazine went on to make a team with: two “Meias” (attacking midfielders), putting both meia armador and ponta de lança into the same position (for example, Cuca and Toninho, pontas de lança in 88, were placed as “Meias” in 89); and three atacantes (forwards), placing both wingers and centre-forwards in the same spot. From 1996 on, another defensive midfielder was added in place of a forward in the final team of the year — both remaining forwards were usually a duo of a second striker and centre-forward).

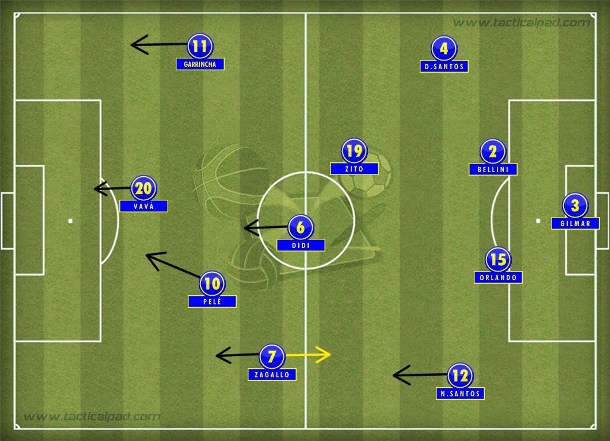

1958 and 1970 Brazil

That foundation was kept throughout the 60’s, 70’s and 80’s, but, we still saw changes, innovations and adaptations in the period, mostly in the Brazilian National Team in World Cups.

In 1958, Zagallo, ponta esquerda (left winger), was brought to the midfield, and Brazil played in a 4-3-3.

Brazil in the 1970 World Cup, as explained by the competent Brazilian journalist, André Rocha (free translation here and everywhere else):

Zagallo, Brazil’s coach in that World Cup, stated another characteristic of that unforgettable team: “We defended in a 4-5-1. Only Tostão stayed upfront. But even he went back, if needed“.

It is usually claimed that the Seleção in 1970 played with five “number 10’s”. In their teams, Rivellino, Gérson (at São Paulo FC in that year), Jairzinho and Pele, played with that number. However, in regards to what really meant to be a “10”, Brazil had four of such players (since Gérson was a meia armador): Rivellino (who also could play as a meia-armador, but he won his only “Bola de Prata” as a ponta de lança), Tostão (although he wore the 8 for Cruzeiro), Pelé and Jairzinho (“I was a ‘ponta de lança’ a number 10”; Rogério was the right-winger for Botafogo).

PELE’S POSITION

Some journalists and football fans, when discussing a “true number 10”, usually mention Maradona, Zidane, Zico, Platini, among others. A few of them define Pele like that. However, from the information reported here and later on, I believe it’s possible to state that Pele was a “true number 10”, like Zico, Platini and Maradona. The more careful reader notices that I did not mention Zidane. Yes, in my opinion, Zizou, in the Brazilian tradition, was closer to the old number 8, the meia armador. Let’s see, the main playmaker of his teams, the French player did not use to enter much the opponent area and scored very few goals (0.19 career average). On the other hand, players in the mold of Zico, Pelé, Platini and Maradona, helped in making plays, but were also great scorers with goal averages considerably superior to Zidane’s in official games: Platini and Maradona with a little more than 0.5 per game; Zico, approximately 0.7; and Pelé, 0.93. Because of that, I consider a mistake to talk about a “true number 10”, as someone supposed to be “the brain of the team” (the main playmaker), because that was the role of “the true number 8”.

1981 Flamengo by André RochaNotice how the traditional tactical base (with small variations) is still there: : volante (Andrade), meia-armador (Adílio), ponta de lança (Zico), ponta-direita (Tita), centroavante (Nunes) and ponta-esquerda (Lico).

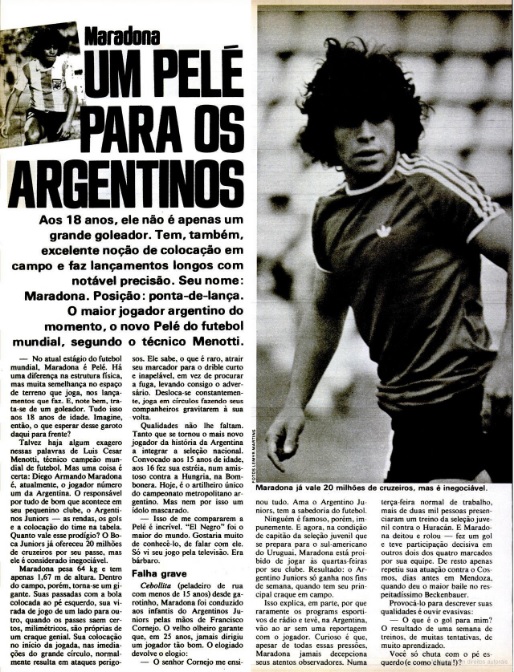

Furthermore, other evidences suggests Pele played in the same position as Zico and Maradona. Both 80’s legends were called “ponta de lança” in Brazil. Regarding Zico, check again the picture of the 1988 “Bola de Prata” and Flamengo’s tactical formation above . As for Maradona, César Luis Menotti, who coached Argentina in the their 1978 World Cup victory, said the following words, reported by “Placar Magazine” in the end of that year (image below — in the article, the 18 year old Diego is called a ponta de lança): “In the current stage of world football, Maradona is Pelé. There is a difference in physical structure, but a lot of similarities in the space in which he plays, in the kind of long passes he makes. And he is a goal scorer”.

Revista Placar, n. 449, 1/12/1978

In their teams, Maradona and Zico always played in advanced roles, behind only one or two forwards. The Argentine, for example, in the 1986 World Cup, highlight of his career, only had Valdano in front of him; and for Napoli, there were two forwards, Careca and Carnevale. Likewise, Zico and Maradona were capable of playing as second-strikers.

See below how similar were the positions of the three legends on field:

Also relevant to reinforce the comparison of Pele to Zico and Maradona, the opinion of the legendary Tostão, “O Rei” teammate in 1970 and, currently, a brilliant columnist:

As we can see, Tostão calls Pelé, Maradona and Zico as ‘Pontas de Lança”. Although he used the word “forward” to describe such position, it is clear, by his explanation, that those players had similar roles to current and recent attacking midfielders like Kaká and Rivaldo.

Moreover, it is important to read the words of Jairzinho, leading scorer for Brazil in the 1970 World Cup: “I was a ‘ponta de lança’, a number 10 (…) Botafogo from that time had Roberto Miranda as the centre-forward. Pelé, at Santos, had Coutinho. Evaldo for Cruzeiro. And so on. None of us was really a forward”.

Well, we have seen that Pele was a ponta de lança, with similar roles as Zico and Maradona. All those three great footballers made plays and scored lots of goals. Hence, I think it is possible to state that the most proper contemporary term for Pele’s position is attacking midfielder, an active player in both midfield and attack, like recently were Kaká and Rivaldo. To corroborate those arguments, it is essential to inform that Pelé himself called himself in his autobiography “an attacking midfielder” (London: Simon & Schuster UK Ltd. 2006. p. 41) and that he talked in an interview about his similarities with Kaká:

Still in that perspective, Cláudio Adão, great centre-forward from the 70’s and 80’s, who played with Pelé in the early 70’s, recently explained, in an interview for “ESPN Brasil”, why he had to change his position in the beginning of his career (I’ve edited this post and added this quote in 07/19/2016):

Pelé can’t be considered a pure forward, because, despite constantly entering the box to shoot at goal, he used to retreat back to defense with a much higher frequency than current footballers from that role (Messi, for example, unlike Pelé, has even played as the most advanced forward in his teams, the “false 9”). In this sense, observe the map done by the French newspaper L’Equipe, showing where Pele touched the ball in the 1970 World Cup final:

Nonetheless, several football all time XI selections put Pele as a forward, or, astonishingly, as a centre-forward. It was not like that during his playing days, as we can see in the yearly World XI in the 60’s, done then by English journalist Eric batty, in the renowned “World Soccer Magazine”. Next 1962 and 1966, respectively, as examples (images taken from the blog “Beyond the Last Man”):

Oddly, Batty chose the outdated 2-3-5 formation, where, between the “five forwards”, two had similar roles to today’s attacking midfielders (playing behind three real forwards, as taught by Alberto Helena). Where was Pele placed? Precisely at the position that today would be the attacking midfielder, behind three forwards. Incongruously, “World Soccer” in 2013, made a worldwide survey among journalists to choose the all time XI, and, disregarding its own history, put Pele in the same section as centre-forwards like Romário, Ronaldo, Van Basten and Gerd Müller. Several journalists even committedthe sin of putting Pele as the most advanced forwards of their “dream teams”. On the other hand, the webpage of Globo (Brazil’s biggest TV station), rightly put Pelé among the attacking midfielders (“Meias”), together with players like Zico, Rivaldo, Rivellino, Ronaldinho and Kaká, in its online survey to choose Brazil’s all time XI; Pelé was the most remembered players with over 306 thousand votes.

Finally, the most convincing evidence, a 2012 interview by the King himself, in wich he clearly states he was a midfilder and not a striker (translated below the video):

“I played the midfield role. I always played as a third man; I was never a advanced striker. I would always come from the midfield, because I helped to defend; everybody can see; just watch it”

There stills lies a question: what role would Pelé have in the most used tactical formations today?

The King would definitely not be a pure playmaker like Iniesta, Ozil and Fabregas, players similar to the meias-armadores (number 8) from the past, main organizers from their team and who don’t score much. In his original position, Pelé could play in a 4-2-3-1 as the central attacking midfielder or as the sole attacking midfielder for the team in a 4-3-1-2. Although not ideal, he would also be effective as a second striker (in some forms of 4-4-2 or 3-5-2), ou even as side forward in a 4-3-3 (not as winger, but as someone who would cut to the middle a lot and would participate in the playmaking there, like Messi, recently, for Barcelona).

Therefore, based on everything I’ve written, I believe Pele was an attacking midfielder, a “true number 10”.

BONUS:

I recommend this excellent video with 100 great goals by the King, posted by youtube channel “Futebol Nacional”:

PS: WRITTEN IN 01/17/2024: I’ve read some comments online, mostly from non-Brazilians, arguing that Pelé only became a true number 10 in the later stages of his career, mainly in the 1970 World Cup. To refute them, I offer the following video from 1969, in which a Reporter asks Pelé about Saldanha’s (the then new Brazilian National Team coach) wish to put him “upfront”; The King shows his dissatisfaction and claims that he has always played “coming from behind”:

Transcription:

Reporter: According to the tactical formation that Saldanha has already defined for the Journalists, you will play upfront, fighting with defenders. It seems that you don’t like this playing style.

Pelé: It is not that I don’t like it (…) What happens is that I’ve played for 15 years coming from behind, and to come and to change my way of playing, just like that, it is not possible.

Jeff

Excellent article with very good work. I am very glad I came across this.

Could you recommend some books on tactics and formations or just your favorite books on football?

Thanks from a fellow fan

Otávio Pinto

Thanks, Jeff. The thing is I basically only know football books in Portuguese. The only one I know in English is “Inverting the Pyramid: The History of Soccer Tactics” by Jonathan Wilson. https://www.amazon.com.br/Inverting-Pyramid-History-Soccer-Tactics/dp/1568587384

Luis

Dude, excellent text!

It’s really a total mistake consider Pele as a center-foward. Your words are right at this point!

But if we see the Pelé full games videos on youtube, we’ll see that he is more like an inside foward or a second foward than a attacking midfielder or an advanced playmaker. He created scoring opportunities more by dribbling and moving on the field than by making through passes. His role was more like Messi than like Kaká.

Zico and Maradona, for an example, they made much more through passes attempts and less shooting attemps than Pelé.

I guess that the “ponta de lança” role doesn’t exists anymore in today soccer, but if we talk about the “pontas de lança” of the past, some would be classified as attacking midfielders and some would be classified as inside forwards (support strikers, second fowards). I guess Pelé would be in the second type.

Otávio Pinto

Thanks, Luis! Good arguments. Some knowledgeable people have that same opinion. But, obviously, based on my article, I disagree. Although I do think he could play as a second forward as well today. What about in the 1970 World Cup, don’t you think he was an attacking midfielder there?

There’s also a portuguese version of this article: http://otaviopinto.com/index.php/2016/07/14/pele-10-tatica/

Wandile

Past 1968 Pele played in deeper rolls then usual because his athleticism and burst of pace were stifled a bit to the injuries. While having some creative duties even then Pele tended to contribute more by beating players then with his Vision and creativity.He was in fact closer to a second striker much like Baggio or Hagi and even then not quite to the extent.

Odiseo

Hello mate!!!

There is a term, the “deep-lying playmaker” … that term is the same like “trequartista” in italian or “mediapunta” in spanish.

This term is applied for those players that is difficult to see if they are midfielders or forward, I mean they are a mixture of both and don’t matter if they play in the sides or the center because is a role and not a position itself.

Players like Diego Maradona, Michel Platini, Zico are “mediapuntas”, I also think Di Stéfano, Johan Cruyff, even Kaká, Rivaldo, Ronaldinho, Omar Sívori, Roberto Rivelino, Téofilo Cubillas, etc… were mediapuntas …. today I think Juan Mata, James Rodríguez, Kevin De Bruyne, Henrikh Mkhitaryan, the Messi from 2015 are mediapuntas.

Pelé was a mediapunta, only from 1968 more or less … but from his beginnings until before that year he was a forward, actually an all around forward because he played everywhere in the attack and in this way he showed his prime from 1958 to 1965 … yeah his years 1968, 1969 and 1970 were very goods, especially the 1969 but I think not better than his version in the other period of time that I told.

So the Pele’s version that is the same than Zico, Maradona, Platini is the Pelé from 1968, but just that version because before that he was a forward.

Another thing … He need to speak very carefully about Maradona because he played everywhere in the attack … the young Maradona played a some kind specie of Forward … probably thanks to that the article said that the 18 years old Maradona played like Pele’s position.

In other hand … the term center-forward is not a striker like today … the center-forward was the player who went down to create the offensive plays like Mathias Sindelar … the center-forward of today would be a mediapunta or very mobile forward … actually Messi playing as false 9 was a center-forward. For that reason I understand when someone called Pele as center-forward.

I agree that Zidane, Özil, etc… aren’t the same than Zico, Platini … they are attacking midfielders while Zico, Platini, etc… are deep-lying forwards.

Finally … for me Pele wasn’t a true attacking midfielder … well only from 1968.

MAXINO ARTILLERO

Pele was an offensive midfielder, who could play center forward, extreme or creator. Pele could be Garrincha, Didi or Vava, but they could not be Pele.

I just saw the Brazil-Mexico match of the 1962 World Cup again and it is clear that Pele plays offensive midfielder. In the final of the Copa Libertadores 1962 is also seen to play well.

Miguel

I think, you confused the terms:

* Deep Lying Playmakers – A playmaker sitting in the first line of midfielders (Pirlo, Didi, Xavi)

* Deep Lying Centreforward – A #9 that goes back to midfield to link attacks and leave his space to being exploted by two forwards making diagonals into the box (Hidegkuti, Di Stefano, Messi).

* Trequartista / Mediapunta – An hybrid between an Attacking Midfielder and a Forward, being involved in the creation of plays and also scoring goals by himself.

baked georgia

great article. it’s very interessing how brazil despite, usually, recognized as creator of the 4-2-4 system, never ever used the 4-4-2 system, usually called “4-4-2 with two lines” or “english 4-4-2”, which is a very similar system.

while in the 90’s, and early 00’s, most brazilian clubs play “square 4-4-2”, internationally called 4-2-2-2. with such a narrow midfield it explains why brazil always had such attacking fullbacks

the difference between an attacking midfielder and a second striker can be many times very slightly, depending only on relative terms from the area. such as “trequartista” for example. baggio and del piero are usually called as second striker, but when it comes to totti… harder to explain

Otávio Pinto

Thanks, Georgia!

“while in the 90’s, and early 00’s, most brazilian clubs play “square 4-4-2”, internationally called 4-2-2-2. with such a narrow midfield it explains why brazil always had such attacking fullbacks”

It does explain indeed!

“the difference between an attacking midfielder and a second striker can be many times very slightly, depending only on relative terms from the area. such as “trequartista” for example. baggio and del piero are usually called as second striker, but when it comes to totti… harder to explain”

It can be. Some people used to call the likes of Baggio and Del Piero as “9 and 1/2”

Asa Lejeune

First time visiting your website, I like your blog!

Benjaminho

Such a fabulous article, thank you! So full of documentation, and visual aids. I have always had a fondness for 4-2-3-1, which I now realize is very like the 4-2-4, with the lance point dropping back. Bruno Fernandes is doing a wonderful job as a “true ten” for Manchester United right now, with Paul Pogba as the 8. 4-2-3-1 seems to have something for each personality to express themselves with. I used to coach youth players, and my gift was to “see” them, find them their place, show them their role, and then help them all work together. Maybe you could do an article of the 5 different coaching templates? lol enjoy your day!

Otávio Pinto

Thank you for such a kind comment. Yes, the modern 4231 (which I agree is a great formation) does indeed look like the old 424. Great to know about Manchester United; I will definetly watch some of their games now.

thank you

I do not speak English well

if you do not mind

I would like a Zico column like this one please..